Judicial Reform

Another example of the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s problematic use of the ‘special law’ provision

August 1, 2024

Ryan Haynie

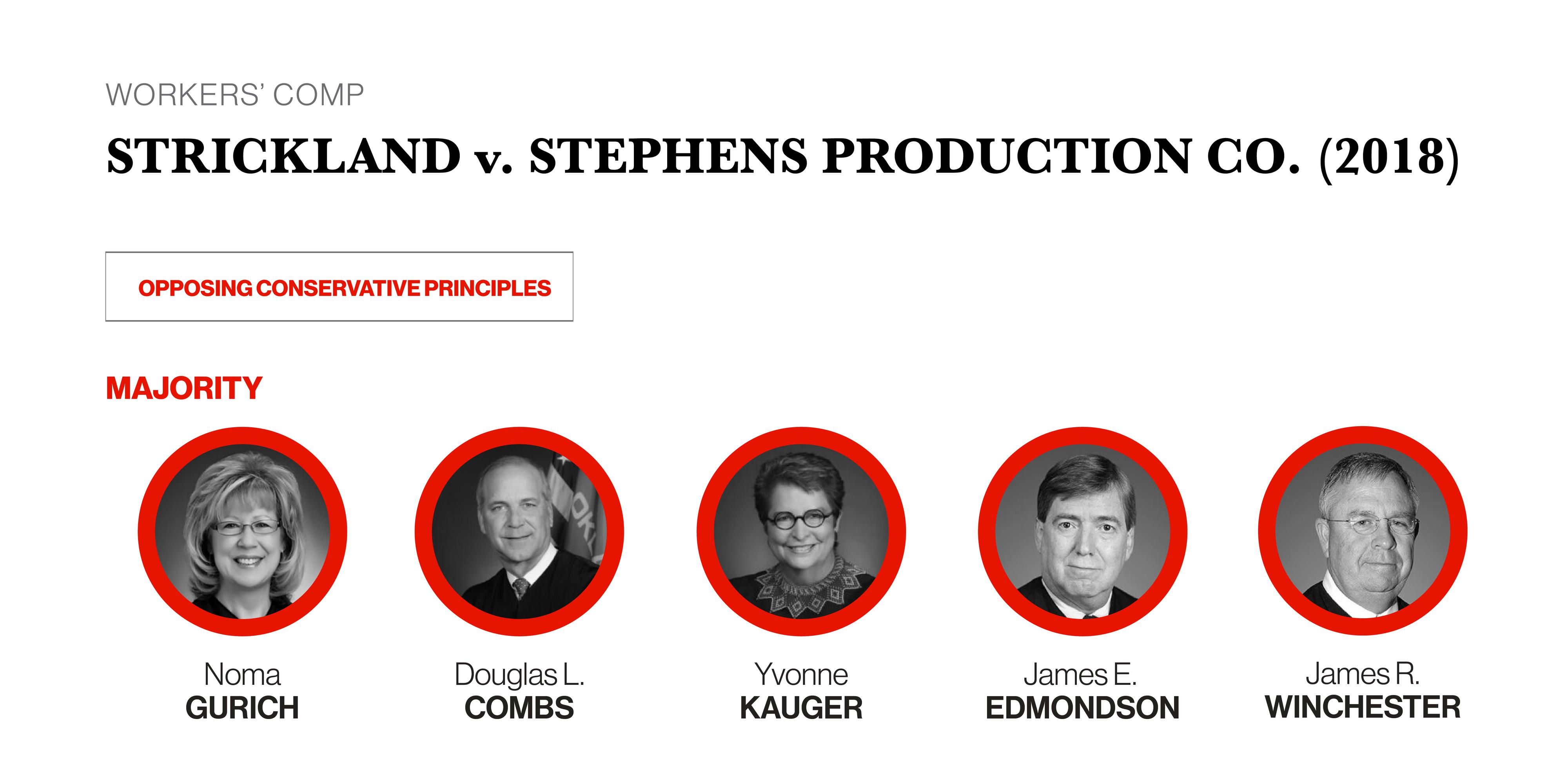

Visit www.OklaJudges.com to learn more about your Oklahoma Supreme Court justices.

The Oklahoma Council of Public Affairs recently highlighted the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s use of the Oklahoma Constitution’s prohibition on special laws to invalidate laws it finds politically uncongenial. That same brand of judicial activism was also on display in a decision to judicially abrogate a sentence of law related to the workers’ compensation reforms in the early 2010s.

The case before the Court dealt with an employee of a trucking company who was killed on an oil-well site. His daughter filed a wrongful death suit against the operator of the well. The operator claimed that it was immune from a wrongful death action because the daughter’s exclusive remedy was under the workers’ compensation law. This law clearly stated: “[f]or the purpose of extending the immunity of this section, any operator or owner of an oil or gas well … shall be deemed to be an intermediate or principal employer for services performed at a drill site or location with respect to injured or deceased workers whose immediate employer was hired by such operator … at the time of the injury or death.” This provision, therefore, makes clear that the decedent must be treated as if he was an employee of the well operator.

In other words, the Oklahoma Legislature made a policy decision to have most oilfield injuries handled administratively through the workers’ compensation system rather than through the adversarial court system. But as in the tort reform case linked above, because this reasonable policy choice got in the way of providing plaintiffs their preferred remedy, the Oklahoma Supreme Court struck down the law as a special law.

The Court’s cases dealing with the prohibition on special laws highlights some problems in its jurisprudence in this area. For starters, how do you define the class? In other words, is the question whether this oil and gas employer is treated like other oil and gas employers or whether it is treated like every generic employer? The Court does not articulate a clear standard for how to define the class—enabling it to characterize this legislative distinction as arbitrary whenever it so desires.

Second, what are the standards for judging whether a special law is “substantially related to a valid legislative objective?” The Court never really says. Who bears the burden of proof? And what does valid mean? Any reasonable objective? Does it have to be compelling? Again, the Court never really says. It just makes distinctions that serve its ends and determines for itself what is a valid legislative objective.

It’s also telling that the Court had previously punted the same issue to the Oklahoma Court of Civil Appeals (OCCA) in Benedetti v. Cimarex Energy Company. In that case, the OCCA found a substantially similar preceding law was not an unconstitutional special law. But the Supreme Court apparently didn’t like the result reached by the OCCA. Without explaining how the OCCA erred, the Supreme Court decided it needed to change the law set by the OCCA.

Readers may see a pattern here. The prohibition on special laws is frequently used by the Oklahoma Supreme Court to strike down laws it deems problematic. Typically, this means problematic for trial lawyers—these decisions tend to expand liability in ways that benefit trial lawyers. Additionally, the Supreme Court often fails to adequately explain its reasoning—in this case, ignoring legal analysis from the OCCA (and reargued by the State). These issues highlight a pattern of illegitimate policymaking by our state’s highest Court.