Health Care, Culture & the Family

Catastrophic rupture

April 8, 2020

Dwayne A. Schmidt, M.D.

A cardiologist looks at the policy response to COVID-19 and its impact on health and human flourishing

As a physician and business owner, I am exposed to and impacted by the COVID-19 virus in a host of ways. As we condition our workplace and our 75 employees to mitigate the risk of exposure to the virus, or the propagation of the COVID-19 virus (or any virus) to our patients with heart diseases, we are also faced with the task of maintaining our economic viability. As a health care provider entity, with the “essential service” of reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality for the people of Oklahoma, we are doing our best to be open in the future, after the pandemic.

As a consequence of being responsibly compliant with the “elective procedure” edicts from our professional societies and the Oklahoma State Department of Health (OSDH), we anticipate a 60 percent reduction in office-based visits, tests, and surgical procedures in the ambulatory surgery center portion of our facility. We are converting as many office visits as possible to telemedicine visits, which is appreciated by many of our patients but inadequate for many more who have ongoing cardiovascular health concerns that cannot be sufficiently evaluated or treated over the phone, regardless of a face-to-face “virtual” visit.

A secondary issue of the telemedicine approach is the potential impact on revenue. For example, neither Medicare nor the commercial insurers have delineated how the usual office copays and individual patient out-of-pocket costs (deductibles and coinsurance with Medicare) will be handled for this service. The initial statements from the insurers and MCR, not yet codified, is that these “fees” will be waived for those encounters. If that is indeed the case, the business will likely have a net loss of revenue for the provision of this service—the office copays and coinsurance dollars is where our only “margin of profit” exists for in-office encounters. Those visits require infrastructure, medical assistants to prepare the charts, scheduling personnel to schedule the visits and potential revisits, and the professionals’ time. This “social distance” clinic visit may in fact be a net negative for the “business” of medicine.

We are certainly hopeful and optimistic that the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and the attendant Payroll Protection Program loan through the Small Business Administration, as well as the significantly underserved need for our services waiting for us at the end of the pandemic, will help us maintain our economic viability. However, my greatest fear is not the direct medical impact of the actual COVID-19 infectious illness over the spring of 2020. My greatest concern is our approach, as a medical and business community, to the fear impact of the infection and the long-term unintended consequences of our reactionary approach. I will mention a few clinical scenarios to add texture to this concern.

Unintended Consequences

My partners and I have diligently elected to screen all of our office cases and invasive procedure cases and reschedule all but those that we deem urgent from a cardiovascular health mortality/morbidity risk perspective. In addition, some of the hospitals where more extensive surgeries (requiring more than 24-hour nursing care) must be done have unilaterally canceled or deferred scheduling our cases, regardless of the acuity of the individual case.

Patients with large, high-risk aneurysms, with an extremely high short-term mortality risk if left alone, have been deferred by the authorities in charge of these facilities (by OSDH edict). Patients with extremely high-risk carotid artery disease and lesions, who unnecessarily risk lifestyle-changing or life-ending strokes if left untreated, have also been deferred. No one can reliably predict when these aneurysms will rupture or the carotid lesions will embolize or occlude. Ordinarily, these cases are considered “highly urgent,” if not emergent, depending on the symptoms. I have personally deferred a growing number of “elective” cardiac catheterization cases in patients with abnormal stress tests and symptoms deemed to be “stable.” Unfortunately, I have already had one of these cases suffer a life-changing heart attack at home.

This situation of health care deferment needs to be very carefully examined and discussed in a more public forum. The current economic dislocation that is happening with the population at large, along with its attendant health-related consequences, also needs a more rational conversation in the public domain. Unfortunately, political expediency and informational biases, in a setting of statistically inadequate information, have created a public policy that I am very afraid could be more lethal than the virus itself.

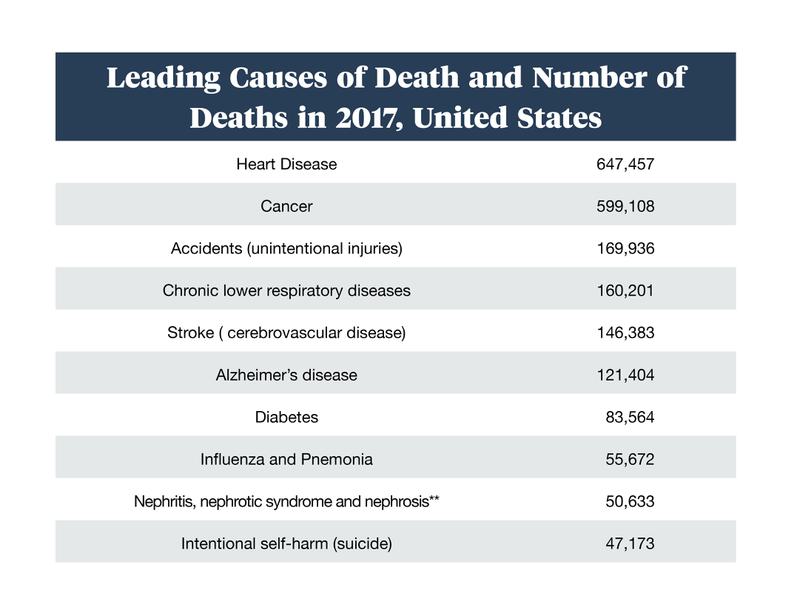

It is very true, in a graphic way, that the COVID-19 virus is having a serious and deadly impact on some of those infected. It is truly a very nasty virus with which we must contend. But the impact of this nasty disease needs to be examined and presented to the public in the greater context of all the other causes for morbidity and mortality in a modern society. The following is such a discussion. The table below presents the leading causes (and annual numbers) of death in the United States in 2017.

*Traffic accidents >40,000

**Chronic kidney disease

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Also, in order to provide additional context—especially for those in the media and government who have compared the COVID-19 pandemic to World War II—it’s worth noting that approximately 400,000 Americans were killed in the World War II effort. The early mortality statistics of this pandemic confirm that it will not have that effect directly. John P.A. Ioannidis, a professor of medicine, epidemiology and population health, biomedical data science, and statistics at Stanford University, suggests in a very exhaustive analysis that the available data points toward a case rate mortality rate of 0.05% up to 1.0%.

Losing Life and Livelihood

Moreover, the loss of employment and the attendant health consequences are being severely overlooked in the current media roundup of this pandemic. The coping-methods hypothesis in this situation is very real and has been studied at great length. People who are unemployed or underemployed have a much greater likelihood of harmful behaviors such as unhealthy eating, tobacco use, excessive alcohol consumption, and even illicit drug abuse. (As an aside, currently in Oklahoma it is easier to buy THC than to get a haircut.)

It has been documented that a population’s BMI (body mass index) will increase during a prolonged period of high unemployment. The incidence of latent illness has also been shown to increase during periods of prolonged unemployment, as a consequence of deferring health maintenance and diagnostic services as a means of saving money for food and shelter. Suicide rates are also known to significantly increase during similar periods of time.

This data was carefully analyzed in 2011 in a very large meta-analysis (“Losing Life and Livelihood: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Unemployment and All-Cause Mortality”) in the peer-reviewed academic journal Social Science & Medicine. The takeaway points of this monumental work are the following:

1. The all-cause mortality for the under- or unemployed versus those employed was 63% higher.

2. The men who were in their “mid-career” age of 40-45 years had the highest mortality (73% increase).

3. Gender was a key variable, with men much more likely to die young, and from suicide.*

What is needed is a truly objective analysis of our current response to COVID-19. I have several concerns regarding the current public policy:

1. People who need disease management for their chronic diseases are being “triaged” in a manner that may impact them greatly, and irreversibly. The “flattening of the curve” public policy may actually increase all-cause mortality in the population by the deferment of treatment of chronic latent health issues.

2. The data on deaths from COVID-19 presented in the media are not being reported in the context of annual death rates from other causes. Moreover, the COVID-19 recovery rates and stories are not being adequately reported.

3. The more than 10 million people thrust into unemployment will likely create a “second wave” of morbidity and mortality that could exceed the direct COVID deaths. This has not been discussed in a cogent manner at the local or national level.

4. The long-term public health costs of a less healthy, underemployed or unemployed population has not been discussed. These costs will be in addition to the costs in the CARES Act.

5. The “life saved versus dollar lost” argument offered to justify the unilateral, government-imposed shutting down of commerce is of suspect validity when the data presented above is considered. Reasonable minds must discuss the issues objectively. The United States didn’t decide that the lives potentially lost in World War II were not worth stopping the advance of anti-Semitism and the collapse of sovereign nations under the Third Reich. Our policymakers are now deciding that our sovereignty as individuals, a state, and a union is not worth one life lost to a unique virus.

6. The “flattening of the curve” public policy, with closing schools and keeping young healthy workers at home, will in fact defer the “herd immunity” that so effectively mitigates diseases such as other COVIDs, H1N1, influenza, etc. This policy will likely enhance the morbidity and mortality of the second wave this winter, prior to the release of an effective vaccine.

In sum, all of these issues need to be discussed in a public format by a broad spectrum of medical professionals, epidemiologists, business owners, and clergy—who hopefully have no motives other than the love of country, community, and family. This discussion must be heard, by our representatives, in a representative democratic society. Americans, and Oklahomans, need to reevaluate our behavior and acknowledge that we are not “subjects” but in fact “sovereigns” in our civil society. If we continue to be sheep in this pandemic, our political leaders will assume the role of wolves.

It is concerning to observe that in our free society, many of the media professionals locally and nationally lack the objectivity and commitment to facts needed to facilitate an open discussion of these issues. The impact of a public policy that (1) increases morbidity and mortality of non-COVID diseases by deferment of treatment, (2) reduces the rate of natural immunity to a morbid infectious illness, and (3) destroys the livelihood of a broad base of the population while creating long-term consequences on public health and health costs desperately needs an open discussion at all levels of the body politic.

Bad news, and the fear-inducing embellishment of incomplete, poorly adjudicated science always sells better than any good news and factual data presented in an analytical manner. The worst we have to fear … is the fear itself.

*In their conclusion, the authors note: “Due caution is warranted, however, as Dorling (2009) suggests that some interventions, such as low-wage work programs, appear to exacerbate the hazard of dying due to unemployment. However, studies suggest that cardiovascular screening programs among the unemployed, interventions aimed at increasing unemployed persons’ awareness of behavioral risk factors (Hanewinkel, Wewel, Stephan, Isensee, & Wiborg, 2006), and stress-management programs (aimed at preventing risk-taking behavior that leads to the observed increase in injury rates among the unemployed) may be particularly beneficial. Studies such as the current one are particularly important in the current economic climate, with many national unemployment rates exceeding 10% and expected to remain elevated for some time. Much work remains to be done using more detailed specifications of unemployment for which systematic data could not be found. Studies should be conducted in developing nations, where welfare and health care systems are much less developed and unemployment may result in more direct threats to a person's health. Future studies should also collect data on unemployment duration, informal labor market participation, sources of support, and other possible mediators beyond those discussed in this paper.”