Judicial Reform

Oklahoma Supreme Court rewrites an insurance contract

August 7, 2024

Ryan Haynie

Visit www.OklaJudges.com to learn more about your Oklahoma Supreme Court justices.

If you thought members of the Oklahoma Supreme Court only make up law when it comes to legislative enactments they don’t like, you’d be incorrect. Though public focus is usually on those cases involving controversial or high-profile legislation, the Oklahoma Supreme Court has proven it’s not above rewriting contracts governing disputes between private parties.

A recent example of this came in Oklahoma Schools Risk Management Trust v. McAlester Public Schools where the issue was whether McAlester Public Schools’ (MPS) insurance contract covered a particular loss. The case involved a water pipe beneath the school that burst and caused damage to the school. The Oklahoma Schools Risk Management Trust (Trust) asked the trial court to declare the incident wasn’t covered by the contract. The trial judge agreed, and the Oklahoma Court of Civil Appeals affirmed that decision.

The insurance contract included two relevant exclusions for coverage. The first—and the one the Court focused on—was an “Earth Movement” exclusion which said the Trust “will not pay for loss or damage caused directly or indirectly by … earth movement.” The second exclusion was for water, including “[w]ater under the ground surface pressing on, or flowing or seeping through foundations, walls, floors, or paved surfaces.”

So the case involved damage from water that came from a pipe below the school and an insurance contract that didn’t cover damage from water coming from “under the ground.” Sounds pretty simple. For most of us it is, but by now we know many justices of the Oklahoma Supreme Court are less interested in straightforwardly applying the law and more interested in making the law what they think it ought to be. And a private contract dispute is no different.

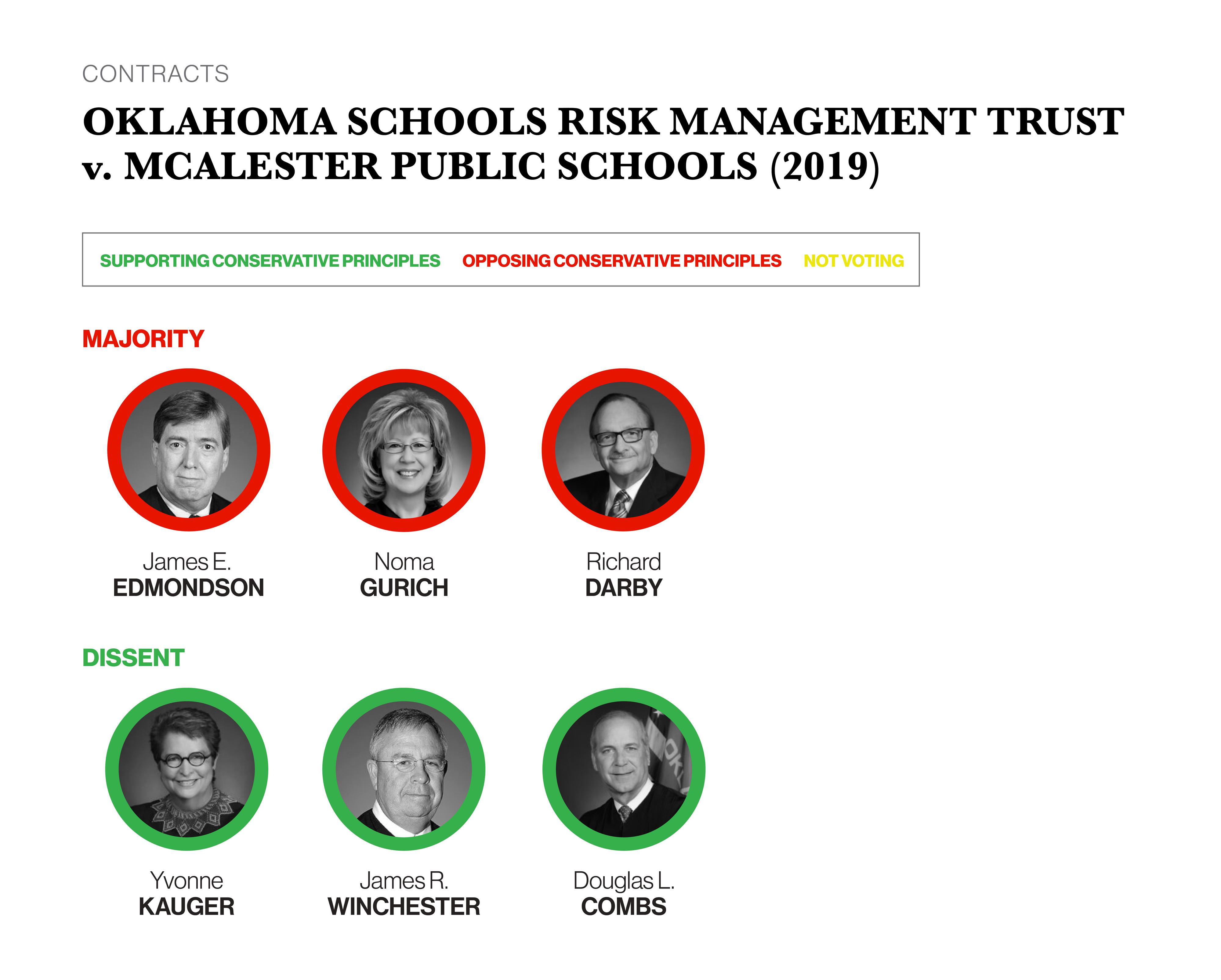

The Court’s majority opinion, authored by Justice James E. Edmondson, found the exclusionary clauses ambiguous. In resolving that “ambiguity,” the majority reversed the judgment of the trial court and the Court of Civil Appeals. The dissent, authored by then-Justice Patrick Wyrick, argued the contract was not ambiguous—leaving most of the majority’s analysis unnecessary. It’s worth quoting from Justice Wyrick’s dissent at length:

The plain text of the contract thus excludes from coverage the event that damaged the school. The only way around this is to declare that the exclusion is ambiguous; so that is what the majority does. … But what about the exclusion is ambiguous? As best I can tell, the majority is lumping the water exclusion in with the earth-movement exclusion and concluding that the exclusion is ambiguous because it does not specify whether it applies to only natural events or both natural and man-made events.

But lack of specificity doesn’t signal ambiguity; it signals breadth. A mother who tells her child to eat his vegetables isn’t likely to be sympathetic when the child eats his carrots but leaves his broccoli untouched because “Mom, you didn’t say that I had to eat my carrots and my broccoli.” This is so because we understand a term to include everything that naturally falls within the term’s plain meaning, unless otherwise specified or unless context dictates otherwise. Even if that weren’t so, the water exclusion’s statement that it applies “regardless of any other cause” strengthens the conclusion that the exclusion applies to all losses caused by underground water pressing up against foundations, regardless of whether that water came from a pipe or an aquifer.

Just as the Court has used the single-subject rule and the rule against special laws to rewrite statutes, many of the justices also have an uncanny ability to find ambiguity in statutes and contracts where none exists. They consistently employ this special power to expand legal liability and assist plaintiffs in their quest for damages. This case is a warning to those who think the Court’s activism only applies to the Legislature. When courts refuse to decide cases on the law and the facts alone, anyone can find themselves in their crosshairs.