Judicial Reform

Oklahoma Supreme Court sets its own policy to allow schools to mask children

July 12, 2024

Ryan Haynie

Visit www.OklaJudges.com to learn more about your Oklahoma Supreme Court justices.

When a lawsuit is brought and the two sides make their arguments in legal briefs and oral arguments, courts generally stick to ruling based on the arguments that are raised. This is referred to as the “party presentation rule,” and it generally discourages courts from ruling on issues that neither side argued. The idea is that this gives each side an opportunity to be heard on the issues that will be part of the court’s ruling.

The Oklahoma Supreme Court often ignores this rule—instead ruling on whatever its members feel justify their preferred outcome. Such was the case in a recent case on school masks.

In the legislative session following the outbreak of COVID-19, the Oklahoma Legislature passed a couple of laws dealing with mask and vaccine mandates in public schools. With respect to mask mandates, the legislature prohibited public schools from instituting one unless the governor declared a state of emergency—something Governor Kevin Stitt had done briefly in 2020. A few parents and the Oklahoma State Medical Association (OSMA) brought a lawsuit claiming the prohibition on mask mandates (absent a declared state of emergency) was unconstitutional under four different legal theories.

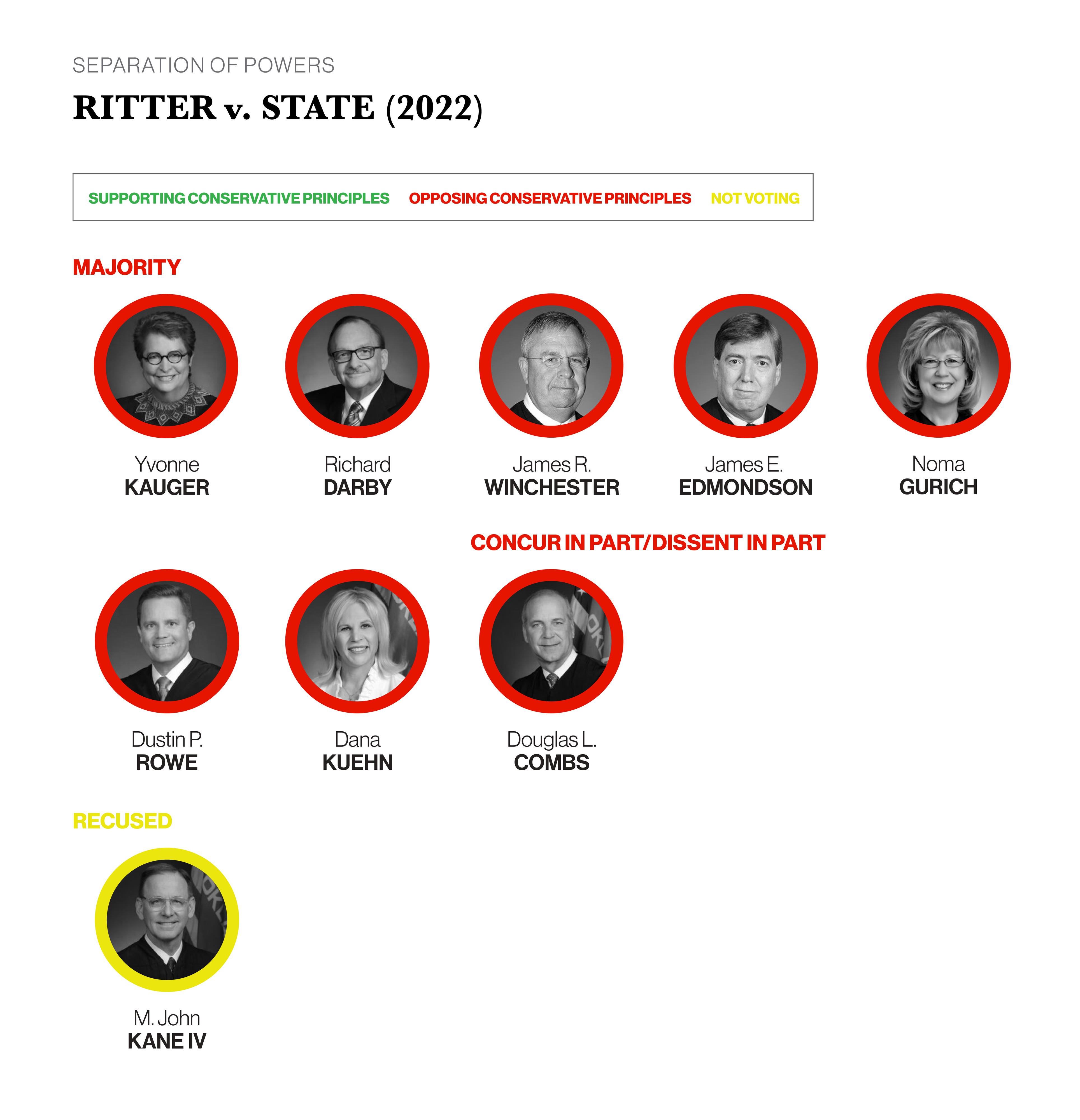

The Court ruled in favor of the parents and the OSMA—allowing schools to force masks on children—but not for any of the reasons the plaintiffs complained about. In other words, the Court broke from the party presentation rule, instead basing its decision on a theory no one argued and no one briefed. Perhaps such an action could be justified if the Court based its opinion on a rock-solid legal theory. But it didn’t. The Court overturned the legislation as an unlawful delegation of authority.

As Professor Andrew Spiropoulos said at the time, the Court was simply incorrect that the law violated the separation of powers doctrine. The Legislature made the policy decision to not allow masks in schools with one exception. Part of that was that the governor had to declare a state of emergency. In fact, the schools also had to consult with local health authorities before instituting a mask mandate, but the Court never said that violated the local school board’s authority.

Professor Spiropoulos also pointed out how common this kind of delegation is in both federal and state law. As an example, I’ve often criticized Oklahoma’s price-gouging laws which go into effect only when the governor or president has determined an “emergency” exists.

The prohibition on mask mandates—absent certain circumstances—wasn’t a delegation at all. It merely put conditions on the exercise of school board power. By reversing, the Oklahoma Supreme Court appears to have severely curtailed the legislative power to regulate the power of school boards. But much to the chagrin of Democrats and teachers’ unions, school boards don’t have unlimited authority and are subject to the authority of the Oklahoma Legislature.

Professor Spiropoulos was willing to give the Court the benefit of the doubt, noting that the justices were “acting in good faith.” That’s unclear. An alternative theory is the justices decided they wanted schools to have the authority to mask children, didn’t feel like the arguments offered to reach that decision worked, and decided to find their own rationale for their decision. And in doing so, it did what it accused the law of doing—taking policymaking power it hasn’t been delegated.