Judicial Reform

Oklahoma Supreme Court struggles with basic vocabulary

June 27, 2024

Ryan Haynie

Visit www.OklaJudges.com to learn more about your Oklahoma Supreme Court justices.

In case anyone wondered whether the Oklahoma Supreme Court would turn over a new leaf in 2024 and begin interpreting the law as written—as opposed to legislating from the bench—it dispelled that notion with its first case of the year. In Stricklen v. Multiple Injury Trust Fund, the Court was asked to decide whether a section of law from the 2013 workers’ compensation reform was a “special law.” You can’t blame the Petitioner for trying. The Oklahoma Supreme Court has struck down a number of that reform’s provisions under the guise that the law was a “special law.”

But the Oklahoma Supreme Court deviated from its favorite tool of statutory destruction in Stricklen and decided it would just completely change the meaning of a word. The law in question allowed an injured worker to recover from the Multiple Injury Trust Fund (MITF) only if the employee had multiple injuries and the latest injury happened “at a subsequent employer.” Because the worker’s injuries all occurred while he was working at the same employer—the Grand River Dam Authority (GRDA)—the MITF argued it was not liable to the worker.

On its own, the Oklahoma Supreme Court found the phrase “subsequent employer” to be ambiguous—despite the parties’ agreement that the GRDA was not a “subsequent employer.” The Court’s majority acknowledge “[t]he term ‘subsequent’ does refer to something following or later than something else,” but then said there’s no reason a “subsequent employer must be a different employer.”

Let that sink in. The Court recognized “subsequent” means something following or later than something else. “Something else” must mean “something different.” If I refer to a subsequent trip, that must mean a different trip than the one that came before it. In fact, the Court’s analysis proved too much. The majority opinion (authored by Justice Edmondson) talked at length about other uses of the word “subsequent” in the statutory framework—the statute also used the phrase “subsequent injury.” But the Court would presumably find it absurd to say that a “subsequent injury” doesn’t mean it has to be a different injury. How could a single injury be a subsequent injury? If all of this is making your head spin, welcome to the club.

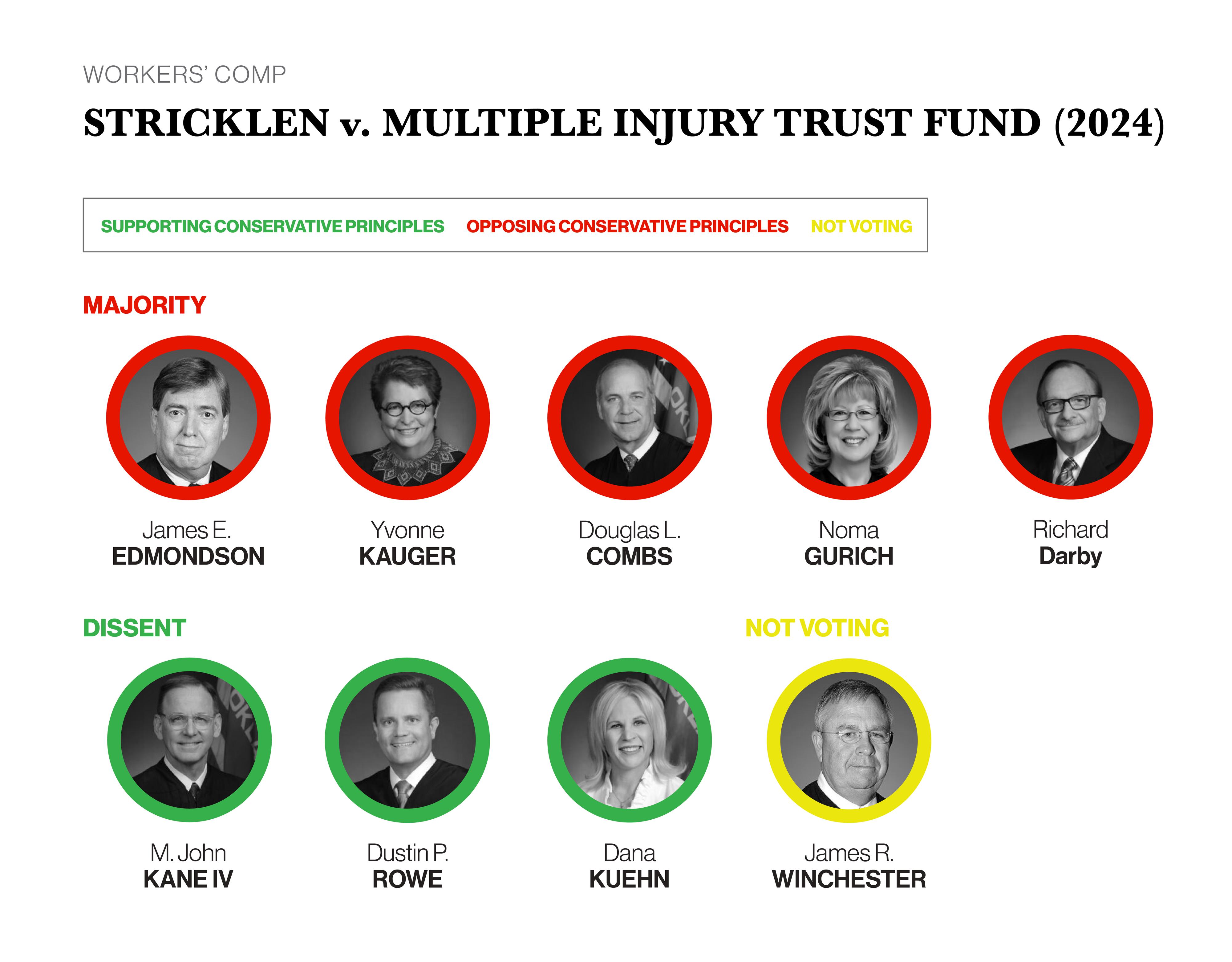

So what happened here? The Court’s majority just couldn’t believe the legislature meant to deprive the plaintiff of a remedy without speaking clearly. But how much more clearly could the legislature have spoken? The fact is, the justices in the majority are rarely—if ever—inclined to find the legislature has limited a plaintiff’s right to claim damages. Even when the legislature has done so.

While the Court didn’t address the special law issue the parties asked it to address, it nevertheless used another familiar tool of statutory destruction to invalidate another provision of the 2013 workers’ comp reform. In the coming months, we’ll highlight other examples of the Court’s activism with respect to this policy and others. Fortunately, three justices—all appointed by Governor Stitt—dissented. And while this is commendable, none of them chose to write a separate opinion explaining why they dissented. I would love to see Justices Kane, Rowe, or Kuehn write an actual opinion taking their colleagues to task for such a blatant abuse of the English language.