Health Care

What's really behind rising hospital prices and insurance premiums?

January 20, 2021

Kaitlyn Finley

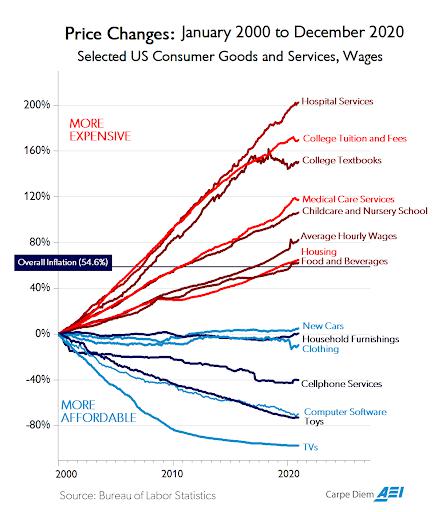

Oklahoma families are feeling the pinch of ever-rising health care costs and insurance premiums. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, average family health insurance premiums exceeded $21,000 in 2020, while hospital service prices have more than doubled over the last couple of decades, outpacing inflation and wage increases.

Let’s examine a few factors behind the mysterious case of rising healthcare costs. As Dr. Keith Smith and Jay Kempton, founders of the Free Market Medical Association often state, when it comes to health care pricing—it’s all smoke and mirrors. It’s nearly impossible for patients to see past the smoke screen of bogus pricing and know what is a true market price.

Behemoth hospital systems and insurance companies routinely play the blame game for who’s responsible for increased health care costs and premiums. But there is little incentive for any entity in the health care space to change the status quo.

Due to a regulation in Obamacare called the medical loss ratio, insurance companies’ profit margins are generally locked in. Depending on the size of the insurance company, 80 to 85 percent of all their expenditures must be paid out for medical claims, not administrative costs. This means the best way for insurance companies to increase profits is to increase the total amount of claims paid out, which in part incentivizes wasteful health care spending.

Once patients hit their deductible, there is little incentive for patients or insurance companies to be mindful shoppers, which also may lead to more unnecessary spending. This regulation has not harmed the large insurance companies; in fact, their stock prices have soared since Obamacare was passed into law. Cigna, Anthem, United Healthcare, and Humana have seen an average increase of 562 percent in their stock prices from January 2011 to January 2021.

Building upon a lack of public pressure for transparency, large hospital systems and drug companies have no reason to be upfront with their prices. In some cases, they have negotiated supposed “better” rates with insurance companies for services or products, but they still won’t give the patient—or the employer who pays for a large portion of their employees’ health care bill—any idea what the product or service will cost.

A number of insurance companies offer price transparency tools but, according to an article in The Wall Street Journal, “In some cases, contract clauses [between insurers and hospitals] prevent patients from seeing a hospital’s prices by allowing a hospital operator to block the information from online shopping tools that insurers offer.” For these members, “shoppable services and price transparency” is empty rhetoric.

Hospital Consolidation and Increased Prices

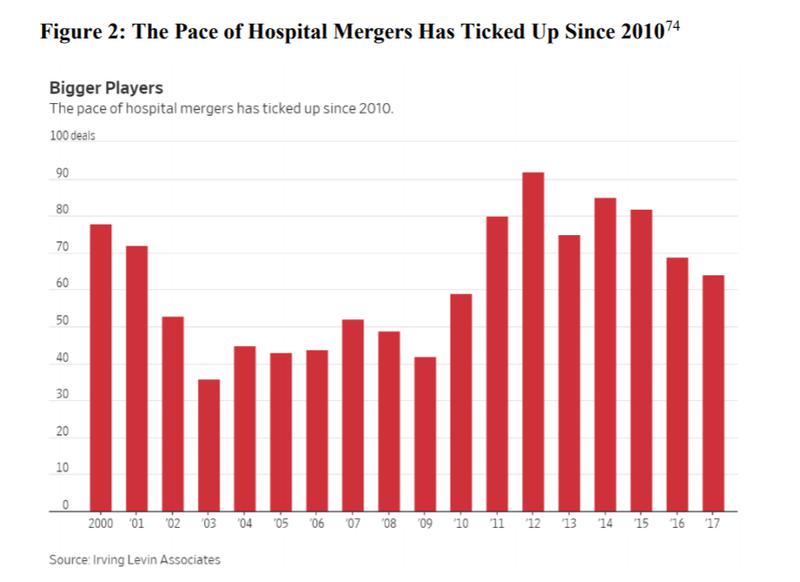

In many large metropolitan areas, hospitals have cornered their market and exercised their leverage against insurers to increase prices. Both conservative and progressive health policy analysts have taken note of hospital systems’ effort to consolidate their market.

According to the Wall Street Journal, “In 2010, the year the Affordable Care Act passed, the annual number of hospital mergers shot up 40% to 59, and the number of deals has remained above 60 every year since, according to Irving Levin Associates, a research firm that tracks health-care transactions.” Research has shown this has affected prices for patients.

A wide body of academic literature compiled by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation found that “[h]ospital consolidation generally results in higher prices. This is true across geographic markets and different data sources. When hospitals merge in already concentrated markets, the price increase can be dramatic, often exceeding 20 percent.”

A 2018 study published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics echoed these results and found that prices at monopoly hospitals were markedly higher than prices at hospitals in areas that had four or more hospitals in one market. Due to the lack of competition, hospitals can (and often do) charge grossly inflated prices for instruments and procedures.

Consider the Gunder Health System hospital in La Crosse, Wisconsin. The hospital routinely charged $50,000 for a $10,550 common knee replacement procedure. OU Medical Center in Oklahoma City charged Sherry Young, a school librarian, $15,076 for four tiny screws for a minor surgical foot procedure.

Allergy skin patch testing racked up $48,329 in charges for Janet Winston, an English professor from Eureka, California. If these patients knew the cost before care was administered, perhaps they would have negotiated better deals or used a different provider. And Ms. Young and Ms. Winston’s cases are not an anomaly. The Kaiser Family Foundation has dedicated an entire project to keep track of inflated surprise hospital bills.

Toleration of High Prices

So why do patients tolerate rising hospital prices, inflated bills, and nearly guaranteed increase in premiums every year? Due to the way our health care finance system is structured, a large percentage of every bill an insured patient receives is covered by insurance companies and employers that subsidize their health insurance.

(According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, approximately 50 percent of Americans receive health insurance from their employer.) That means patients don’t immediately feel the pinch of their high hospital bills and higher hospital service prices also give insurance companies justification to raise premiums.

Promote True Price Transparency

Once the mystery behind health care pricing is revealed, it’s obvious to see the players within the space don’t want to change the game. Strong forces are needed to change the status quo.

That’s why the Oklahoma legislature needs to be proactive and advance legislation that will protect patients’ pocketbooks and encourage Oklahoma hospitals to be upfront with prices. In most cases, patients should never receive a “surprise” medical bill for their care. OCPA supports legislation that encourages medical providers to be upfront with costs and provide a good-faith estimate for patients whether they are insured or not.