Health Care

Medicaid expansion could shift some federal costs to Oklahoma

September 5, 2019

Ray Carter

Under the federal Affordable Care Act (ACA), better known as Obamacare, states that expand Medicaid to cover able-bodied adults are given $9 in federal funding for every $1 in state funding spent on the expansion population. Supporters argue that high federal match makes the program a financial windfall for state governments.

But members of the legislative Healthcare Working Group learned Wednesday that one part of Medicaid expansion would involve the federal government offloading costs onto state taxpayers.

Under the ACA, Medicaid can be expanded to include able-bodied adults earning up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). The law also provides taxpayer subsidies, on a sliding scale tied to income, to help individuals purchase private policies off a federal exchange. Those subsidies are provided to people earning between 100 percent and 400 percent of the federal poverty level.

The overlap between those two groups—individuals earning between 100 percent and 138 percent of the federal poverty level—has resulted in an outcome that financially penalizes states that expand Medicaid.

“The federal government has since said, ‘If your state expands Medicaid, then those people up to 138 percent of federal poverty are no longer qualified for tax credits on the marketplace,” said Oklahoma Deputy Secretary of Health Carter Kimble, an appointee of Gov. Kevin Stitt.

For example, he noted Wisconsin’s Medicaid program covers adults earning up to 100 percent of FPL. But in doing so, Wisconsin officials receive only the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) provided for the traditional Medicaid program, which is about a 60-40 split in Oklahoma today.

“There are states currently that pay regular match for that group just so they don’t pick up the 100 to 138 (percent of FPL group),” Kimble said.

Data presented by Kimble showed an estimated 85,000 uninsured Oklahomans may land in the category of those earning between 100 percent and 138 percent of FPL. Although now uninsured, those individuals currently qualify for federal insurance subsidies that would allow them to purchase coverage at heavily subsidized rates.

Affordable Care Act subsidies for policies bought on the federal exchange are funded entirely by the federal government with no state match. As a result, when states expand Medicaid to cover those same individuals earning up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level, a portion of the cost of coverage is shifted to state governments.

“Other states have seen a move from the private marketplace, the healthcare.gov federal marketplace,” Kimble said. “That move is a product of the fact that you’re no longer eligible for the tax credit, not a product of the employer dropping coverage.”

It is also estimated that 19,000 of the currently uninsured individuals in Oklahoma are already qualified for Medicaid. If those individuals join Medicaid after an expansion, Oklahoma will have to pay the state matching rate for traditional Medicaid, rather than receive the 9-1 match provided for the expansion population.

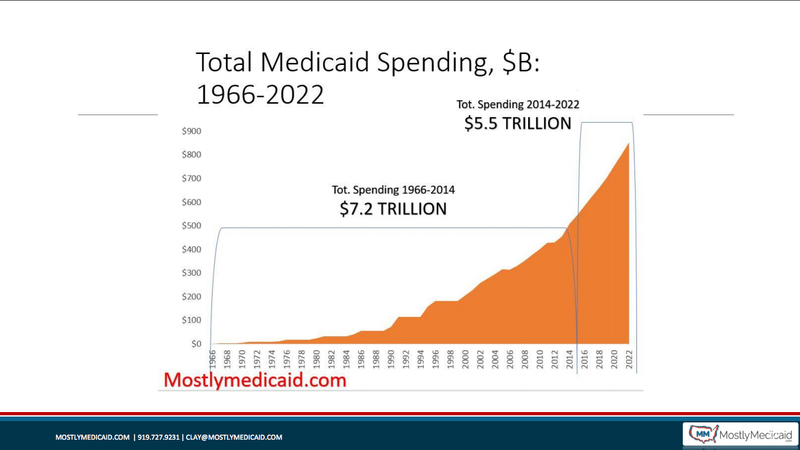

Lawmakers were also given an eye-popping look at Medicaid’s long-term financial trajectory.

Clay Farris, practice lead of client services for Mostly Medicaid, a consulting firm, noted that Medicaid’s nationwide spending totaled $7.2 trillion from 1966 to 2014, including both state and federal funding. The program is projected to spend $5.5 trillion total from 2014 to 2022.

“We’re going to have spent almost as much in eight years as we did in the first 50 years,” Farris said, saying that is a trajectory “that cannot be ignored.”

As the cost of Medicaid surges, it requires the diversion of more money from other government functions, such as education, transportation, and public safety, he said.

“Medicaid does crowd out all of your priorities,” Farris said.

Farris urged lawmakers to incorporate managed care into Oklahoma’s Medicaid system to control costs and reduce the growth of the program’s expenses. Currently, 40 other states either use managed care in their Medicaid programs or have adopted reforms to incorporate it into the system.

While lawmakers discussed managed care at length, the rapid escalation of Medicaid spending—and the long-term implications for state finances—caught the attention of several lawmakers in attendance.

“This slide paints a completely, I will say, irresponsible trajectory for our nation, financially,” said Sen. Greg McCortney, an Ada Republican who co-chairs the Healthcare Working Group. “Why would I do this? Short of just suspending my belief in everything I know about finances, why would I sign my state up for a program that is clearly going to drive us into bankruptcy?”

“We’re tied in right now for the 90-10 split, which some people have said, ‘Boy, that’s a great deal,’” said Sen. John Haste, R-Broken Arrow. “But isn’t reality that the 90-10 split is probably short-term looking at how those costs are escalating, the number of dollars that we’re talking about? We start out at that level, but our costs are going to go beyond the 90-10 split: 85-15, 80-20, or maybe eventually at the 60-40 that it is today for traditional Medicaid.”

“Whatever you are being told you will spend on expansion, multiply it by two, three, four, whether that’s the per-member level or how many will enroll,” Farris said. “And that doesn’t even get at if you maintain that FMAP at 90 percent.”

Gov. Kevin Stitt has vocally opposed expansion of the traditional Medicaid program, a stance Kimble reiterated during Wednesday’s meeting.

“You could, if you wanted to, expand traditional Medicaid up to 138 percent of federal poverty,” Kimble said. “I can safely say, from the governor’s perspective, that is not an option.”