Education, Law & Principles

Motion Picture Association opposes Oklahoma library book ratings

December 8, 2022

Ray Carter

The Motion Picture Association (MPA) has indicated it may sue Oklahoma schools if a state senator’s proposal to use a G/PG/R rating system for school-library books is implemented.

The MPA said use of its rating system is unconstitutional and argued that use of the famous ratings would also violate the MPA’s trademark.

In a press release issued earlier this month, state Sen. Warren Hamilton announced he has requested a bill that would establish a system to rate books rather than ban them from public school libraries. The system would follow the standard movie ratings of G, PG, PG-13, R, and NC-17.

Hamilton said a rating system would give parents a better understanding of the materials their children are reading and allow them to provide parental guidance when necessary.

“This rating system is simple, effective and already widely known,” said Hamilton, R-McCurtain. “This would sort books without restricting them and is a way for everyone to be on the same page about what is and isn’t appropriate for kids at different age levels to be reading.”

Hamilton said the legislation would allow a year for books to be rated, with those rated R or NC-17 placed in a restricted area. Elementary school libraries would be limited to books given a G or PG rating.

No specific bill language has been unveiled yet as the bill has not been filed.

In a Dec. 6 letter of response sent to Hamilton, Kathy Bañuelos, senior vice president of state government affairs for the Motion Picture Association, objected to his proposal.

Bañuelos wrote that use of the MPA’s rating system would “violate the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution” and also “violate the MPA’s rights in the federally registered trademarks it holds for its ratings symbols (‘G,’ ‘PG,’ ‘PG-13,’ ‘R,’ etc.).”

The Classification and Rating Administration (“CARA”), a division of MPA, gives films a G, PG, PG-13, R, or NC-17 rating. Bañuelos noted the rating system was established “to provide moviegoers and parents with advance information about the content in rated films, to help them determine which motion pictures may be appropriate for their children to see.”

But Bañuelos then claimed that courts have ruled use of such a rating system is unconstitutional when mandated by law rather than voluntary action in the private sector.

However, most of the cases cited by the MPA have significant differences with Hamilton’s proposal.

One case involved an Oklahoma state law enacted in 1971 that exempted from a state obscenity statute any commercial motion pictures that have a seal under the Production Code of the Motion Picture Association of America. A court struck down that law as “an unconstitutional delegation of legislative authority” to a private organization.

However, as described in his release Hamilton’s proposal does not necessarily involve outsourcing the process of rating books to an outside entity.

Another case cited by the MPA dealt with a city ordinance that prohibited children from attending movies rated R or higher without an adult.

And a third case cited by the MPA involved a state college that refused to allow college funds to be used for the showing of a movie given an “X” rating (the precursor of “NC-17”). A court held that the college had violated the First Amendment.

But Hamilton’s bill involves distribution of materials to minors, not college students, and state law specifically defines “child sexual exploitation” to include “causing, forcing or requiring any child to view any obscene materials, child pornography or materials deemed harmful to minors.” State law defines “obscene material” to include “any representation, performance, depiction or description of sexual conduct, whether in any form or on any medium.”

Several school-library books that have prompted parental objections have included visual depictions of masturbation and oral sex. The MPA letter did not address whether it views anti-obscenity laws to be unconstitutional when dealing with children.

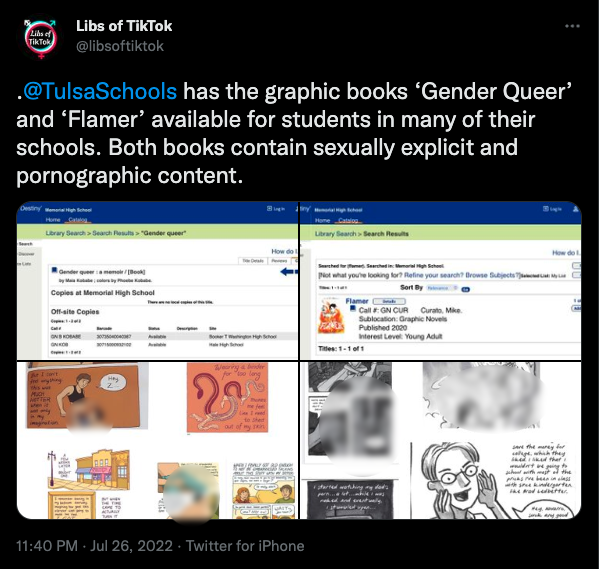

Some school-library materials have drawn bipartisan criticism. After it was learned that school libraries in Tulsa Public Schools included copies of “Gender Queer” and “Flamer”— which both include visual images of sexual acts— State Superintendent of Public Instruction Joy Hofmeister, a Democrat, issued a statement saying the two books contain “inappropriate, sexually explicit material” and are “pornography that does not belong in any public-school library.” She called for the books to be removed from the school library.

Much of Bañuelos’ letter focused on the MPA’s trademark interest in its movie-rating system.

“All the MPA Rating Marks are widely known and famous throughout the United States as designating motion pictures rated by CARA,” Bañuelos wrote. “These Rating Marks are incontestable and may only be used by permission and authority of the MPA, and only in connection with motion pictures that have been rated by CARA.”

She suggested use of the movie-rating system would confuse parents.

“The application of the Rating Marks to books not actually rated by CARA, as mandated by your proposed legislation, would constitute a blatant infringement of MPA’s trademark rights, leading to widespread confusion among students, parents, as well as library patrons and the public, about whether those books were indeed rated by CARA,” Bañuelos wrote.

If Hamilton’s proposal becomes law, Bañuelos said “the state of Oklahoma, school districts, and any private entities (e.g., book publishers) that affix the Rating Marks on books not actually rated by CARA would potentially be liable for traditional trademark infringement and dilution, among other things.”