Education

Brandon Dutcher | August 11, 2019

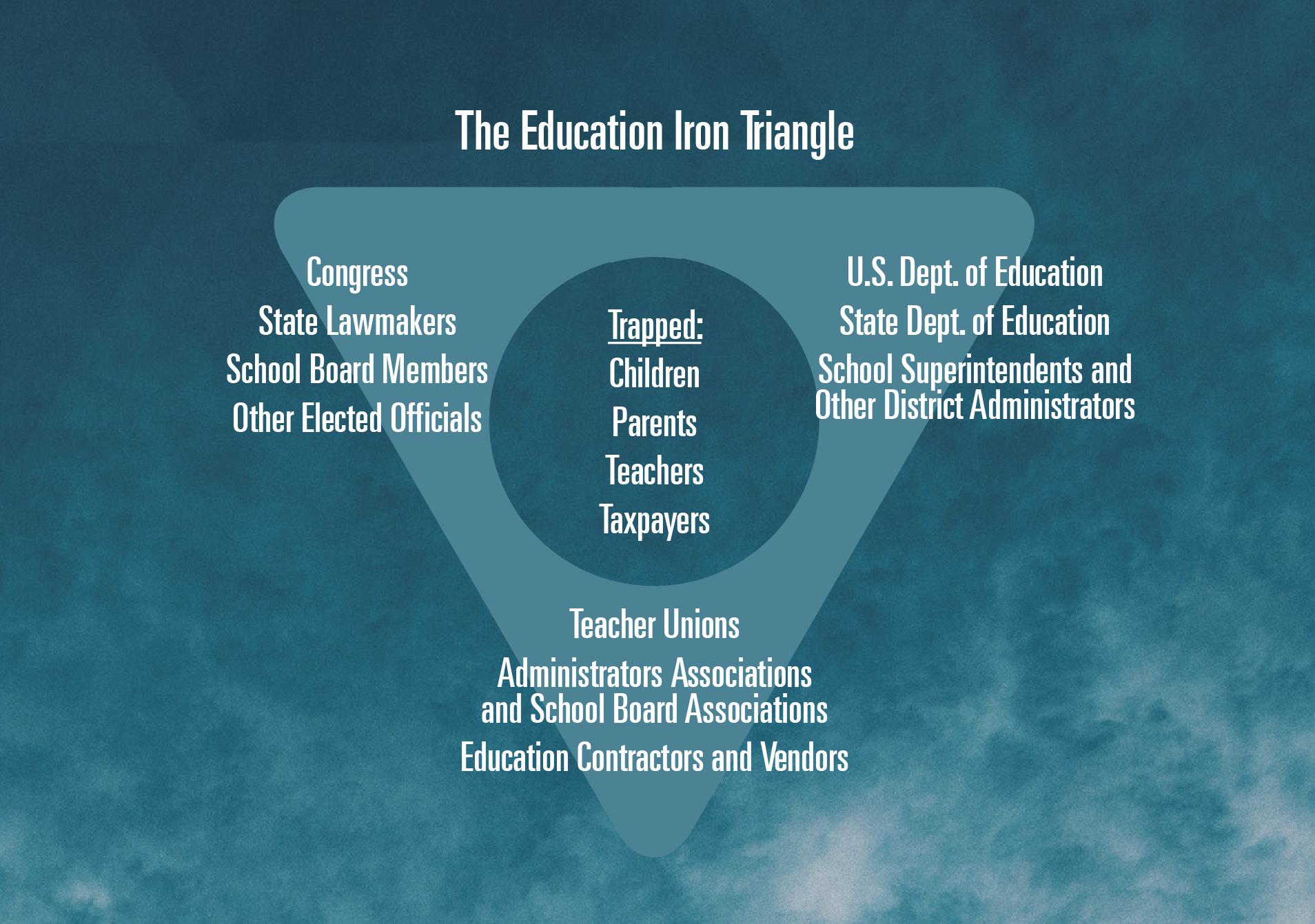

Powerful iron triangle resists parental choice

Brandon Dutcher

Oklahomans favor policies which give parents more educational options. However, enacting those policies has proven to be difficult. A simple metaphor can help explain why.

In their book "Teachers versus the Public: What Americans Think about Schools and How to Fix Them" (Brookings Institution Press, 2014), scholars Paul E. Peterson, Michael Henderson, and Martin R. West write:

Triangles are the strongest, most rigid, most solid, of basic geometric forms. … Triangles relentlessly resist change. That’s why the three-legged stool is sturdy, the tricycle stable, and the ancient pyramid an architectural triumph. … When iron is cast as a triangular form, the object is tough, strong, and powerful.

For political analysts, the iron triangle is the perfect metaphor for characterizing one of the strongest, most stable, and most pervasive aspects of American politics—the connection among producer interests, elected officials, and actions taken by government agencies.

Let’s have a look at the three sides of this triangle as applied to education policy, starting with the base.

Producer interest groups. “Metaphorically speaking, representatives of producer and occupation-based interest groups … constitute the base of an isosceles triangle,” the authors write. “They serve hard, highly concentrated, powerful interests. Those interests connect and support the triangle’s other two sides.” In Oklahoma, these interest groups include the Oklahoma Education Association (OEA), Oklahoma State School Boards Association (OSSBA), Cooperative Council of Oklahoma School Administration (CCOSA), Oklahoma PTA, and other organizations.

Elected officials. “By means of steady communication and financial contributions, representatives of producer groups build close relationships with the senators and representatives who serve on relevant committees in Congress, state legislators who act in the same capacity at the middle tier of government, and local officials who serve on special boards and commissions that affect the well-being of the producer group.”

This is certainly the case in Oklahoma, where “for too long Republican legislative leaders have carelessly placed members with close ties to the failed education establishment in important committee posts concerning education funding and management,” as OCPA distinguished fellow Andrew Spiropoulos has noted.

Local school boards are also part of this triangle’s left side. Typically they are hostile to parental choice, in large part because they are populated by officials elected at odd times—which is just the way the producer interest groups like it. “The people who vote in a stand-alone, low-turnout election are disproportionately those individuals who have a personal stake in the outcome and are organized to further these selfish interests—special-interest groups,” Spiropoulos explains. “Candidates supported by teacher unions and the rest of the school establishment are likely to prevail when everyone else isn’t paying attention.”

Government agencies. “The third side of the triangle is formed by the government agencies that produce goods, regulations, and services of interest to the producer group,” the book’s authors write. Superintendent Joy Hofmeister and the state Department of Education are not friendly toward parental choice, and many local superintendents are openly hostile.

In summary, then, “an iron triangle encloses a space that is virtually impossible to penetrate,” the authors write.

As a metaphor, it captures the reality that producer groups excel at discovering channels of communication that access information unavailable to the general public. Iron triangle politics are quiet, operating beneath the radar, almost in secret. To capture special benefits from the public trough, the producer group needs to belly up to the goodies while squeezing others to the side.

Producer groups succeed in insulating policy decisions from external pressures because they have the focus and resources to pursue their goals effectively; the attention of the general public, in contrast, is too episodic and scattered to have an impact, except in times of crisis. … Ordinarily, the iron triangle operates quietly—at the public’s expense.

Which is why Oklahoma’s political leaders continually increase education spending—as they did in 2019—without implementing widespread parental choice. As Spiropoulos points out, they simply don’t have “the energy, desire, or intellectual capacity to fight the powerful education establishment. It’s just easier to give them what they want.”

[An earlier version of this article appeared in 2014.]

Brandon Dutcher

Senior Vice President

Brandon Dutcher is OCPA’s senior vice president. Originally an OCPA board member, he joined the staff in 1995. Dutcher received his bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Oklahoma. He received a master’s degree in journalism and a master’s degree in public policy from Regent University. Dutcher is listed in the Heritage Foundation Guide to Public Policy Experts, and is editor of the book Oklahoma Policy Blueprint, which was praised by Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman as “thorough, well-informed, and highly sophisticated.” His award-winning articles have appeared in Investor’s Business Daily, WORLD magazine, Forbes.com, Mises.org, The Oklahoman, the Tulsa World, and 200 newspapers throughout Oklahoma and the U.S. He and his wife, Susie, have six children and live in Edmond.