Education

Teacher hiring devastated by emergency 'common sense shortage'

Greg Forster, Ph.D. | October 5, 2017

Oklahoma’s education establishment and click-addicted media benefit from public hysteria about a “teacher shortage” and “emergency certifications.” But the general consensus is that the empirical research does not find evidence of educational value—at all—to teacher certification requirements. These arbitrary and educationally useless requirements do nothing to improve educational quality, and much to hinder schools’ ability to hire teachers.

The latest tactic of Oklahoma’s education old guard—the teacher and staff unions and their allies—is to use overheated rhetoric to whip up the appearance of a “teacher shortage.” The Oklahoma campaign was even covered in the Huffington Post this summer. The old guard wants across-the-board salary increases, protection from accountability, and other perks. But the evidence they cite not only doesn’t establish there’s a shortage, it actually points toward giving schools the one thing unions don’t want them to have: flexibility to hire teachers without arbitrary and educationally useless certification requirements.

I’ve been in the education policy business since 2002, and in all that time, a year has not gone by when the old guard wasn’t blaring about a supposed teacher shortage. When the economy is good, that causes a teacher shortage because allegedly underpaid teachers now have the opportunity go into higher-paying jobs. When the economy is bad, that causes a teacher shortage because allegedly underpaid teachers need to go into better-paying jobs to pay the rent. (Actually, federal data show teachers are paid well, but never mind.) When education reform is stalled, that causes a teacher shortage because no one cares about education. When education reform is active, that causes a teacher shortage because reform is a big hassle for teachers.

New moons cause teacher shortages because teachers have accidents driving in the dark without moonlight. Full moons cause teacher shortages because teachers become werewolves.

Claims about the causes are always changing, tailored to whatever is in the news. The claim that there’s an urgent, emergency shortage that we need to address right now never goes away.

On the current rotation of this merry-go-round in Oklahoma, we are, as always, hearing a lot of isolated anecdotes that don’t establish a widespread problem. If you want hard data, they do exist. A 2015 study commissioned by a partnership of state agencies, including the Oklahoma Department of Education, found that the imbalance between teacher supply and demand in the state was trivial—less than a percentage point out of alignment.

The only hard datum presented by the old guard is the state’s recent approval of exceptions to teacher certification requirements in 631 cases. These exceptions allow schools to hire teachers who don’t meet the requirements for traditional certificates.

This is not evidence of a teacher shortage. But if it were, it would point to the need to relax the state’s educationally counterproductive certification requirements. These requirements do nothing to improve educational quality, and much to hinder schools’ ability to hire teachers.

These exceptions are being described as “emergency” certifications. This term has been adopted not only by the old guard but by many others, including some of their critics. I suspect it comes into wide use not only because the old guard and the click-addicted media benefit from public hysteria, but also because the schools seeking permission to make these hires think they’re more likely to get it if their need is described as an emergency. However, the state refers to these simply as “exceptions” to the standard certification requirements. This more neutral description might permit a more careful analysis.

The first thing to know about these exceptions is that they are unevenly distributed. They are geographically concentrated in specific places, and also concentrated among specific types of teachers. For example, while anecdotes are circulating that create the impression the shortage is hitting special education, state data collected by Baylee Butler and Byron Schlomach of the 1889 Institute show that none (“0.0 percent”) of the certification exceptions has been granted in special education.

If these exceptions are evidence of a problem, the obvious thing to do is target our response to the particular localities and disciplines where the overwhelming majority of the exceptions are being granted. That way Oklahoma can solve the problem it actually has, not some other, imaginary problem.

Ha, ha! Just kidding. The obvious thing to do is raise teacher salaries across the board, shut down accountability systems statewide, and give the old guard all the other things it wants. Such measures will have only a very indirect effect on the localized and specialized areas where certification exceptions are being granted. But that’s not what teacher shortage hysteria is ever about.

Leaving that issue aside, the other important thing to know is that standard teacher certification requirements have long been shown to have no educational value. Many empirical studies have been conducted on this question over a long period of time. The general consensus is that these studies do not find evidence that there is educational value—at all—to teacher certification requirements.

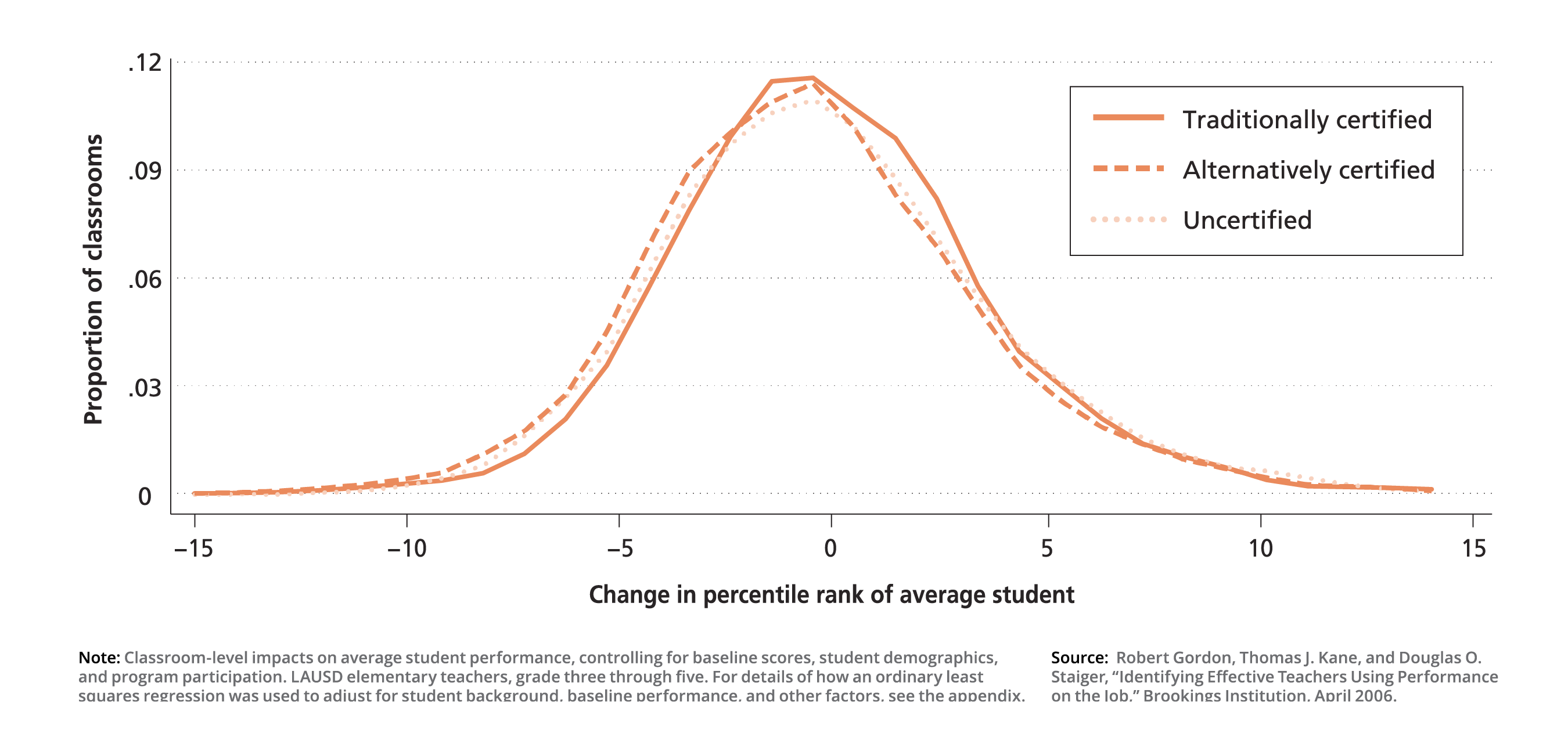

One review of the evidence by a team at the Brookings Institution produced a chart plotting three lines: math scores of students whose teachers had traditional certification, alternative certification, and no certification. The lines overlap almost perfectly; there’s virtually no difference. Reformer Matt Ladner calls it the “Super Chart,” because of its enormous implications for education policy.

If these requirements are educationally useless, why do we have them? Because a lot of people make money off them—the people in education schools and elsewhere whose services are required if you want to get a certificate. Their work makes no apparent contribution to educational quality, but certification requirements keep them in business. They are an important part of the old-guard lobbying coalition, as the present hysteria illustrates all too clearly—unions and education schools scratch each others’ backs.

It all comes down to trust. Do we trust schools to use their own judgment when hiring teachers? Or do we think that if we give schools freedom to hire and fire, they’re going to foolishly hire and retain bad teachers?

Lawrence Baines, an education professor at the University of Oklahoma—in other words, a man for whom the certification requirements are a matter of job protection—wrote in The Oklahoman that the teachers being hired by schools under certification exceptions are like people who forge phony medical degrees. They “may be geniuses or they may be psychopaths, but there is no way of knowing. These folks are unvetted.”

Someone should ask him what he would think of medical schools if a large body of research conducted over decades failed to find evidence that people with medical degrees make better doctors. While we’re at it, we should also ask him why he thinks Oklahoma’s schools would hire psychopaths.

Greg Forster, Ph.D.

Contributor

Greg Forster (Ph.D., Yale University) is a Friedman Fellow with EdChoice. He has conducted numerous empirical studies on education issues, including school choice, accountability testing, graduation rates, student demographics, and special education. The author of nine books and the co-editor of six books, Dr. Forster has also written numerous articles in peer-reviewed academic journals, as well as in popular publications such as The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and the Chronicle of Higher Education.